CoreWeave, the upstart GPU cluster datacenter operator that was formerly a relatively small cryptocurrency miner based in Roseland, New Jersey has filed its S-1 form with the US Securities and Exchange Commission to do an initial public offering. And that has a lot of people – those thinking of investing in GPU datacenters, those thinking of investing in stock in companies that run such datacenters, and those who buy capacity at such datacenters to run their AI workloads – doing a lot of math.

The S-1 forms that are the first part of the dog and pony show when a company goes public are always fascinating, and CoreWeave, which has only been at this for three years, is no exception.

The company is one of the so-called “neoclouds” that is not at all interested in supporting generic infrastructure workloads or traditional enterprise applications and their databases on its cloudy infrastructure. CoreWeave, which perhaps should be called GPUWeave, is only interested in supporting AI training and inference workloads.

The company was founded in 2017 as Atlantic Crypto and did Ethereum mining in a datacenter in Secaucus, New Jersey where hedge funds, trading firms, and stock exchanges also do their processing. This is no accident since co-founders Michael Intrator (its chief executive officer), Brian Venturo (its chief strategy officer), and Brannin McBee (its chief development officer) were involved in the trading of various kinds of financial and energy commodities before they got together with the Ethereum gig. When cryptocurrency tanked in 2018, the three pivoted to building AI datacenters, and the company has grown exponentially since then.

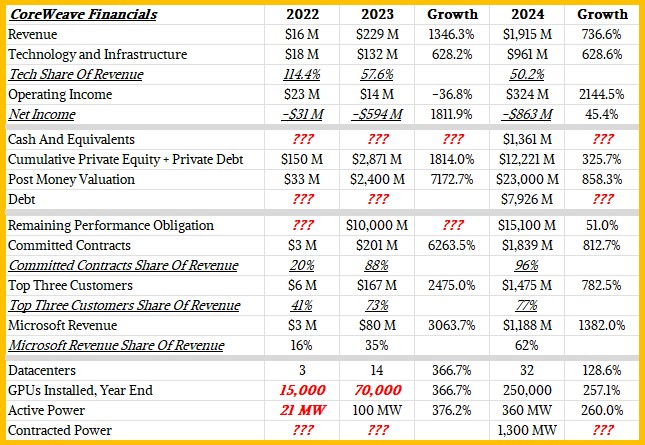

To save you some time, we have poured through the S-1 and consolidated the relevant financial and technical details of the CoreWeave business as revealed:

Over the past three years, between the end of 2022 to the end of 2024, CoreWeave has grown its GPU fleet to a very impressive 250,000 compute engines. Most of these, the company says, are variants of the original “Hopper” H100 GPUs from Nvidia, but there are some H200 versions with more memory and some GB200 versions paired with the “Grace” CG100 processor from Big Green. CoreWeave has also taken delivery of some of the first NVL72 rackscale systems based on Nvidia’s “Blackwell” GPUs and the same Grace Arm server processors, which as the name suggests puts 36 CPUs and 72 GPUs in a shared memory system that spans a rack.

We think that the estimated value of the GPUs in the CoreWeave fleet, which is now spread across 32 datacenters with 360 megawatts of active power, is around $7.5 billion and we estimate further that turning those GPUs into systems required somewhere on the order of $15 billion in capital expenses. Which explains where most of the ginormous pile of $12.22 billion in private equity and private debt and another $7.93 in debt that CoreWeave has raised has gone. The rest is the cost of datacenter facilities, sales, research and development, and general costs, we presume, with $1.36 billion left in the bank at the moment.

That back of the envelope math may or may not jib with a category in its S-1 that it calls “Technology and Infrastructure,” which came to $960.7 million in 2024, up by a factor of 7.6X compared to 2023. We hope this will be explained further as CoreWeave gets closer to IPO, because we know for sure that 250,000 GPUs cost a heck of a lot of money – more than these line items show.

Everybody is making a big deal about how CoreWeave grew revenues by 13.5X in 2023 and then grew it again in 2024 by 8.4X to $1.92 billion. This is phenomenal growth, particularly if you ignore than CoreWeave was under water to the tune of $593.7 million in 2023 and its losses expanded by 1.45X to $863.4 million last year. By our eye, it looks like if CoreWeave grows half as fast in 2025 and can triple its operating income, it could actually be a profitable company.

But then we come to find out that Microsoft is its largest customer and accounted for 62 percent of the company’s revenues in 2024 and seems to be in the mood to be less ebullient about its AI spending as partner OpenAI shifts to its own Project Stargate infrastructure for the same reason that many enterprises are repatriating their datacenters: Cloud infrastructure is expensive compared to owning it yourself. So while that $15.1 billion in remaining performance obligations – which means contractual agreements to buy GPU instance capacity on the CoreWeave datacenters – is great, it might be mostly Microsoft and it might end three years from now if the average contract length is around four years as the S-1 says it is.

Last year, three customers accounted for 77 percent of CoreWeave’s revenues. Which is also a bit concerning. We are admittedly in the early days of the GenAI boom, but we will be watching in the wake of the IPO how this number, along with the revenue and profit trends, changes over time.

How Much Money Can CoreWeave Make?

If you have 250,000 GPUs across 32 datacenters spread around the globe, as CoreWeave does, you have 2.19 billion GPU-hours to peddle in a year with 365.25 days, which works out to 8,766 hours per GPU. That is a lot of hours, and if they were perfectly utilized and every hour of the year was sold at a price of $49.24 per hour for an eight-way GPU instance, as the current CoreWeave price for an H100 instance is, then that would generate $13.49 billion. So in theory, without adding another GPU, CoreWeave can drive 7X the business it turned in during 2024.

But alas, as CoreWeave shows in the S-1, these GPUs do not work at perfect efficiency. According to its analysis, the typical GPU running AI workloads has a computational efficiency of somewhere between 35 percent and 45 percent of peak theoretical performance. There are lots of reasons why this is the case – architectural issues where compute, networking, or memory are out of balance, software is not accessing hardware features correctly, and so forth.

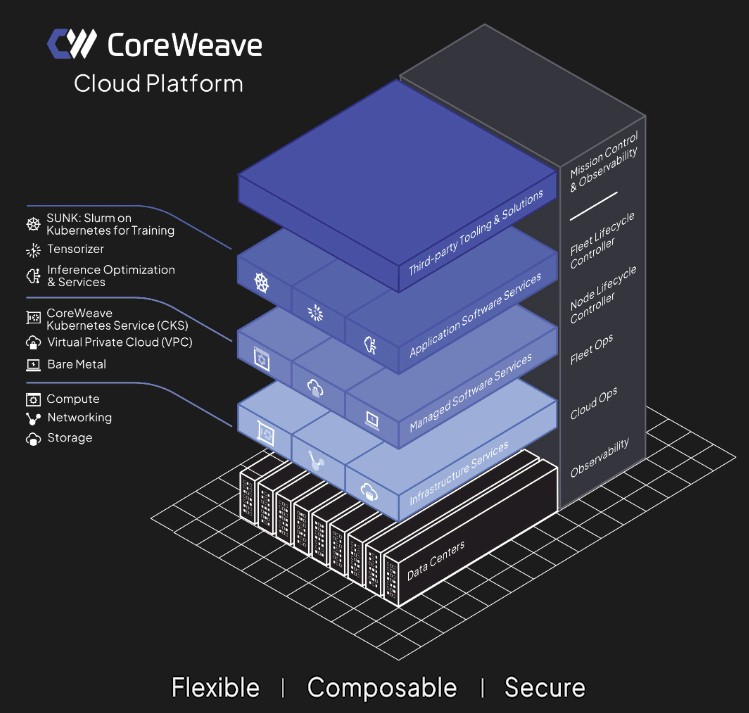

CoreWeave is known as a GPU cloud provider, but the secret sauce of its business – aside from being the first company to use its own GPUs, which have not lost value, as collateral for more loans to buy more GPUs – is the software stack called the CoreWeave Cloud Platform, which stacks up like this:

This is an interesting mix of cloud and HPC infrastructure, as you will no doubt see, and it is akin to the mixture of containers and job scheduling that pioneered the approach two decades ago at Google with its Linux containers and Borg job scheduler and container management system, the latter of which inspired Kubernetes directly.

The CoreWeave software stack starts above bare metal provisioning with virtual private cloud network provisioning, which provides multitenancy with security. On top of that is a managed Kubernetes container service. Nothing strange here. Perfectly big standard cloud.

On top of this comes an inference and optimization service, which as far as we know does not have a clever name so we will call it Inferizer, which makes it consistent with a tool that runs next to it that has a clever name called Tensorizer. This Tensorizer is a tool that sure sounds like it is based on GPUDirect for Storage from Nvidia; it is able to load AI models from storage to GPU memory “from a variety of different endpoints,” as the S-1 put it.

Wrapping around this is a tool called SUNK, which is short for Slurm on Kubernetes for Training – yes, we know that abbreviation doesn’t work. It should be SOKFT, or even more precisely if you want to call it Simple Linux Utility for Resource Management on Kubernetes for Training, which would be SLURMOKFT. This is, it seems, the main feature that allows CoreWeave to get more AI training and inference throughput out of its Nvidia iron. SUNK allows the popular HPC job scheduler to run atop Kubernetes. The latter pods up the AI training model so it can be spread across a GPU cluster, and the former allows multiple AI jobs (presumably multiple training jobs as well as inference) to be run side-by-side and managed.

This is exactly what Google did with Borg and its follow-on, Omega, so many years ago. You can give different jobs different priorities and have the cluster push more work through the system in parallel.

With these and other features of the CoreWeave Cloud Platform, the GPU cloud provider brags that it can push the computational efficiency of AI training jobs by 20 percent or more compared to the more generic clouds like Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services, and Google Cloud running the same Nvidia GPU hardware. That pushes the computational efficiency up to between 55 percent and 65 percent, which about as good as it gets in bursty systems that need quite a bit of computational headroom to deal with spikes.

Here is the thing. If you size your AI cluster using peak compute capacity, you will think you will get X performance but you will get around 40 percent of X, and that means you will need to actually consume 2.5X as many GPU-hours as you budgeted for to do a certain amount of work. Just try to explain that to the CFO. . . .

But with the numbers cited by CoreWeave, at the midpoint of 60 percent computational efficiency, you will take 67 percent more time to complete the job than you think, but that is a hell of a lot lower than 2.5X. It also means that based on peak, you might be thinking that those 250,000 GPUs will drive $13.49 billion in twelve months to do a certain amount of work, but it will actually take 20 months to do it on the CoreWeave cloud (driving $22.48 billion in revenues) and more like 30 months on the other cloud builders who charge twice as much for an H100 GPU-hour and which will drive more like $67.44 billion over those two and a half years.

Doing work faster at an inherently lower cost per unit of performance should be an easy sell. We look forward to seeing what kinds of margins CoreWeave can get away with. It looks like those 32 datacenters have around 8,000 GPUs each, which is plenty big enough to train a respectable model. But they may be asymmetrically distributed across the CoreWeave datacenters for all we know.

What we find interesting is the fact that Microsoft is apparently hard up for GPUs to either help OpenAI to train its GPT models or to do its own training because OpenAI is hogging so many GPUs on the Azure cloud that Microsoft needs to go outside for them. Interestingly, Microsoft charges twice as much to use the H100 GPUs on its own cloud as does CoreWeave at list price. The difference in price is, we think, partly opportunistic on the part of Microsoft and partly due to the wide variety of storage, database, and application services Microsoft offers on Azure. Or, CoreWeave is selling this stuff too cheap to try to drive up utilization on its nascent cloud.

We will know which scenario it is after CoreWeave gets a few quarters under its belt as a public company.

Anyway, the timing of the IPO has not been set, but the idea is to sell somewhere between $3.5 billion to $4 billion of stock to generate some more cash. The company’s founders have sold $488 million of their Class A shares and are already rich, and according to this TechCrunch report have less than 3 percent of the remaining Class A shares. But the three have around 80 percent of the Class B shares, which have ten votes per share and give them majority control of the company even after CoreWeave goes public.

Be the first to comment